It was a good reading month, full of Stars. (Stars: a fixed luminous point in the night sky which is a large, remote incandescent body like the sun.)

I like noticing how books I’m reading relate to one another. In this case there was a distinct theme of houses—how the places where we live reflect our interiorities (or not), house our most sacred creative lives (or not), reflect our politics and values (or not).

I took Marguerite Duras’ book Writing to Northampton (while my daughter & friends roamed the streets) and read it outside the Haymarket Café in the sun. I thought of how I used to come to this cafe as a lonely teenager, pilgrimage to Raven Used Books, and buy slender second hand paperbacks, including some of Duras’—The Lover, The Ravishing of Lol Stein.

But I never read this one, and I’m glad. I like savoring Writing now that I am a middle-aged woman, a writer myself, with a house to live and write in. The book is about the house Duras has settled into in Neauphle-le-Château in southern France. She writes: “This house became the house of writing. My books come from this house. From this light as well, and from the garden. From the light reflecting off the pond. It has taken me twenty years to write what I just said.”

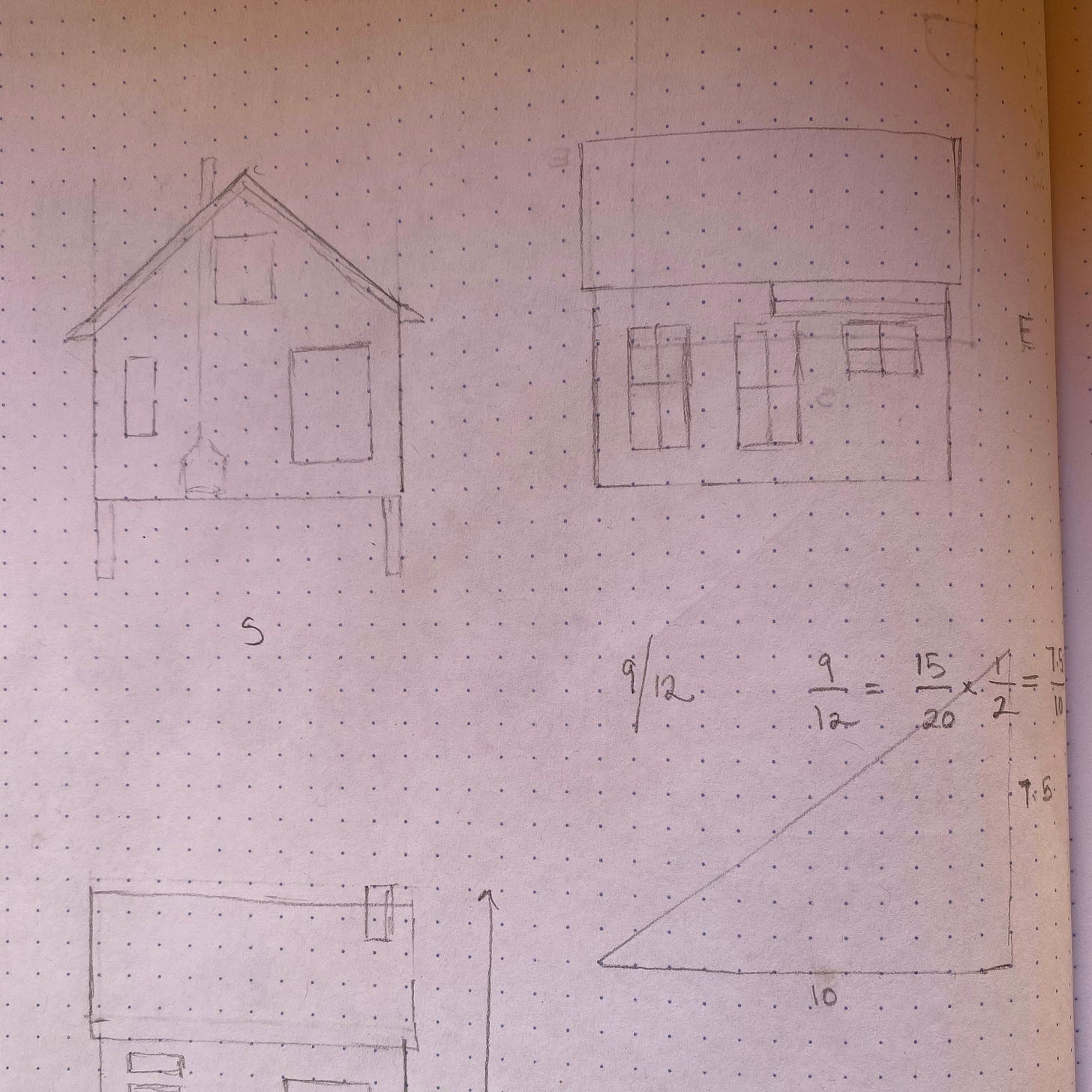

As someone who has written in a variation of the same house since when I was sixteen (I built a cabin which became a larger cabin which later became my house) I like the notion that our books are shaped and born of the rooms and gardens and light and flora and fauna of where we live.

She also writes about the authenticity that is born from the solitude a house can protect: “This is what makes writing wild. One returns to a savage state from before life itself. And one can always recognize it: it’s the savageness of forests, as ancient as time.” A few pages later she continues, “I often find others’ books “clean,” but often as if they derive from a classicism that takes no chances.”

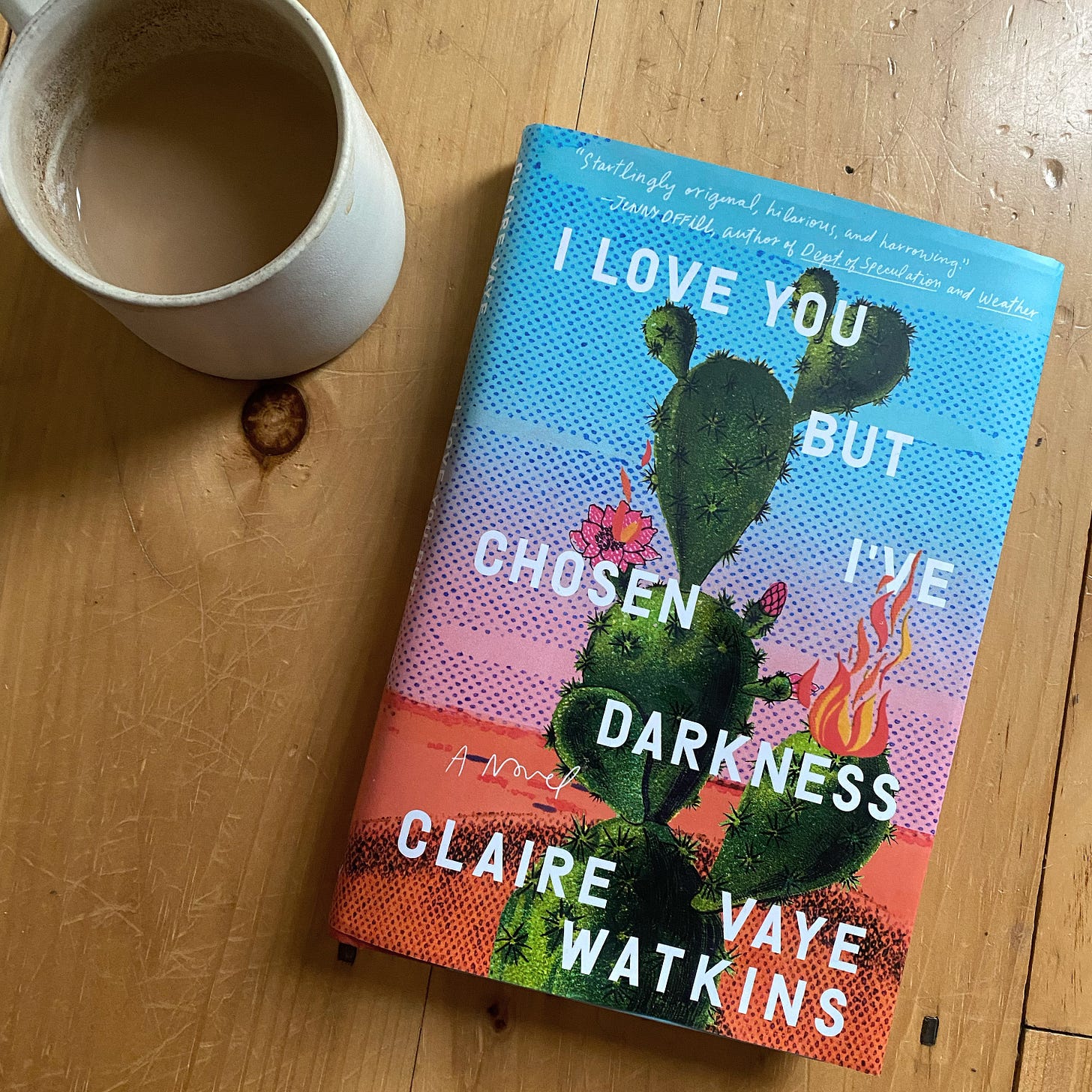

A few days later I read Hillary Kelly’s extraordinary profile of Claire Vaye Watkins in the L.A. Times. I hope you will read the piece in its entirety. It’s profound and moving. And I noted that Watkins echoes Duras as she’s discussing what she’s hungering for in books these days: “An immediacy, close to the bone, like this cost the person a lot to write, and they put on the highest spit shine, but they don’t lose any of the rawness of the discovery, of the surprise.” And then I read Watkins luminous, raw, explosive novel I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness itself.

Some books feel holy to me, and this is one. I cried, ached, rooted, felt reborn. Like Watkins, the Claire of the story has checked all the boxes of traditional American notions of success (published books, won awards, landed the tenure teaching track of dreams, married well, bought a house, had a beautiful child), and yet she feels dead inside. Claire does not feel at home in the suburban, heteronormative, maternal, domestic, professional life in which she has found herself, and so she breaks out of those boxes, one by one, leaves it all behind, and returns the desert—the source of her love, trauma, autonomy, joie de vivre.

The writing is as wild and un-contained as the emotional and physical landscapes Claire returns to. (It feels very much tapped into the ancient forests within, to borrow Duras’ language.) Like Watkins and Duras I pine for wildness, risk and experimentation in the work I read, and I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness answered that call and then some. It made me think about how our traditional domestic houses are often limited, stifling, deadening, and how are our traditional narrative styles are sometimes the same. It made me wonder what a jailbreak might look like—both in life and in literature. Claire shows us.

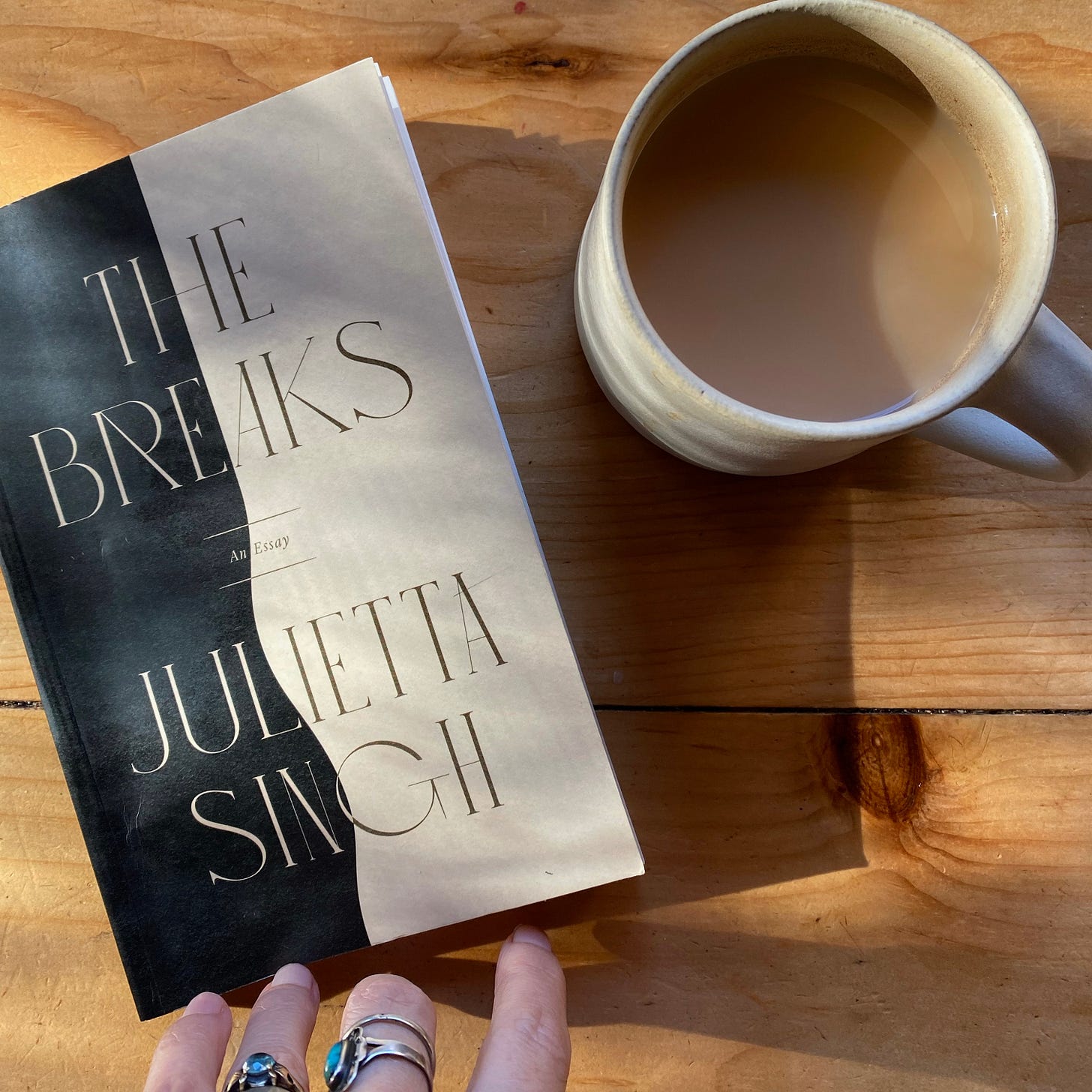

And then, as if in another impeccably timed answer to those simmering questions, I read Julietta Singh’s tender and smart book-length essay, The Breaks. This book-length essay is a letter to Singh’s daughter about growing up in this country amidst an escalating climate crisis and racial tension and violence.

I loved many things, but my favorite section was about how the houses of our lives (the architectural structures we live within) meet or do not meet our internal needs. As I physically build a creative space of my own (with a small loft for sleeping), I loved reading Singh’s own architectural processing.

Singh, who is queer, falls in love with a man and has a child. Despite their radical politics and theoretical ideals, they find themselves purchasing a small house and falling into heteronormative expectations of merging. But it doesn’t work for them, and they have the wherewithal and courage to say so. Soon they create their own rooms for sleeping and working, and not long after they decide a family duplex will work better for them: separate living spaces joined by an external staircase. They soon find that they share most meals together, their daughter flows back and forth between the spaces seamlessly, and they have not only rooms but houses of their own. Singh writes: “For us, the duplex held a different kind of potential, an opportunity to live our lives with the solitude we each yearned for and the adjacency we never stopped desiring. Together apart, apart together.”

So much of heteronormativity is rooted around the physical house of a traditional nuclear family: a master bedroom in which both parents sleep, a shared kitchen, a shared living room. As a writer and introvert who forever pines for more personal space, I have long questioned the limitations of this architectural norm—why not rooms of one’s own? (Not a new concept, of course, but often still difficult to pull off and fight for.) How about apartments or cabins or houses of one’s own? Does love necessitate or demand this all-immersive merging? What would it look like to reimagine the architectural possibilities of partnership?

In the end of Watkin’s novel the Claire of the story has moved out of the house she shares with her husband into a space of her own in the desert, and Watkins, in the L.A. Times piece, has purchased and moved into a house outside Joshua Tree. Duras writes, from her house of solitude, “Writing comes like the wind. It’s naked, it’s made of ink, it’s the thing written, and it passes like nothing else passes in life, nothing more, except life itself.”

Each of these women has chosen a house of their own: a place to be autonomous, to be alone, to be with others when they choose, to create. For me, I’m hoping for my own unique architectural variation. Like Singh I’m interested in how we can redefine architectural spaces within the framework of loving relationships. How might we make partnership more capacious—more supportive of solitude and the wild creativity it breeds?

I wonder, dear writer, about your houses. Your spaces. Do they reflect and invite your ancient forests? Your need for solitude? If not, I invite you to read each of these books, and dare you to imagine how they might do so.

Thank you for reading Them Stars! Subscribe if you want to receive these in your mailbox. Share if you’re inspired. Leave a comment if you want to join the conversation—I’d love to hear your thoughts.

PS: If you enjoyed this, press the little heart so that I don’t have a vulnerability-induced heart attack. Gracias!

I loved this essay. “What would it look like to reimagine the architectural possibilities of partnership?” Very inspiring and provocative. I’d like to design an architecture studio around this concept.

A trip to the bookstore for Duras' Writing is now on the list for today. Every piece of this resonated with me.